Last September probably the most exciting (and exhausting) thing that has ever happened to me took place. Ang Truscott and Debs White from Fibre Arts Take Two and Gary Weston from Sphagetti Weston came to the studio to film an online workshop. The result is Sensing Place, and it is coming out in the next couple of weeks. The workshop covers many of the things that I do within my own practice, and it centres on experiencing the world around us using the senses of sight, sound and touch.

I have titled the workshop Sensing Place because I love how the two words, sense and place, can have a different meaning depending on how they are put together. Sensing Place, puts the emphasis on the word sense which is the way the body understands what’s going on around it. We are also going to be exploring our environment to understand a Sense of Place which is either the fundamental character of a place, or the meaning people give to it, or, perhaps more often, a mixture of both.

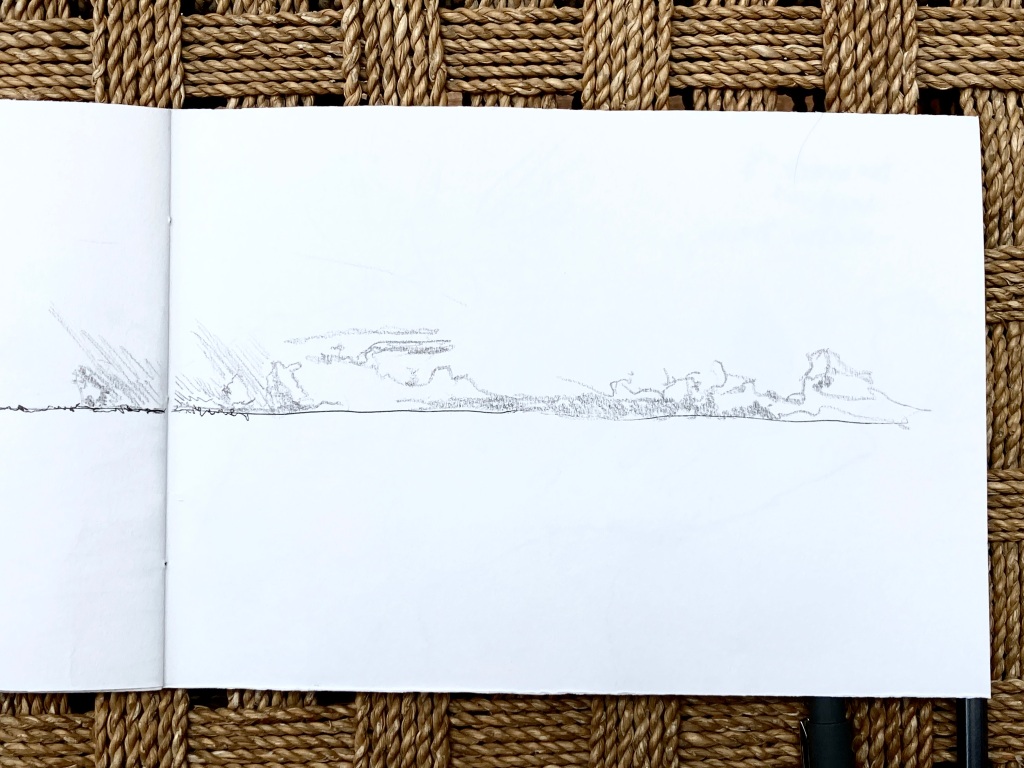

Sketchbook work with drawing, mark making and writing

The workshop is about your landscape, your perception of it using the senses of sight, sound and touch, your documentation of those perceptions and finally, your articulation of it through the things you make.

Make collage – both paper and cloth

In this workshop we investigate three of the five senses – the senses of sight, sound and touch. Although we understand and experience the world using all the senses simultaneously, I begin by presenting each sense to you individually (although you will find that it is just about impossible to do so and one the other senses will inevitably creep in). This is so that I can introduce ideas and techniques to you gradually. You will practice these, and then at the end of the workshop I ask you to put into practice everything that you have learned and start to make work that combines all the senses. You’ll start with the familiar sense of sight, go on to visualising sound and then we’ll consider touch. Finally, I will be asking you to see sound, hear space, hear movement, feel sound etc.

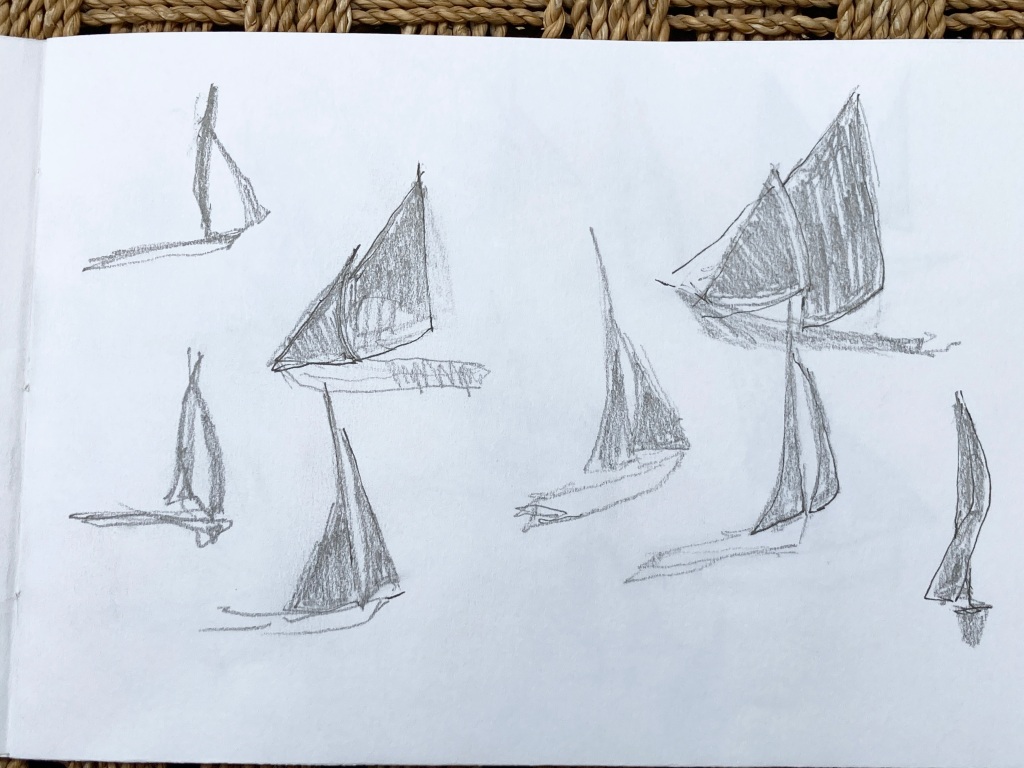

Draw sound

‘By sitting still and taking the time to look and to listen, to breathe, to think and to feel, I believe you can understand your surroundings more completely. By consciously observing and then writing and drawing about your experiences you are more able to comprehend the finer detail, the repetitions and rhythms, and the colours of the world around you.’

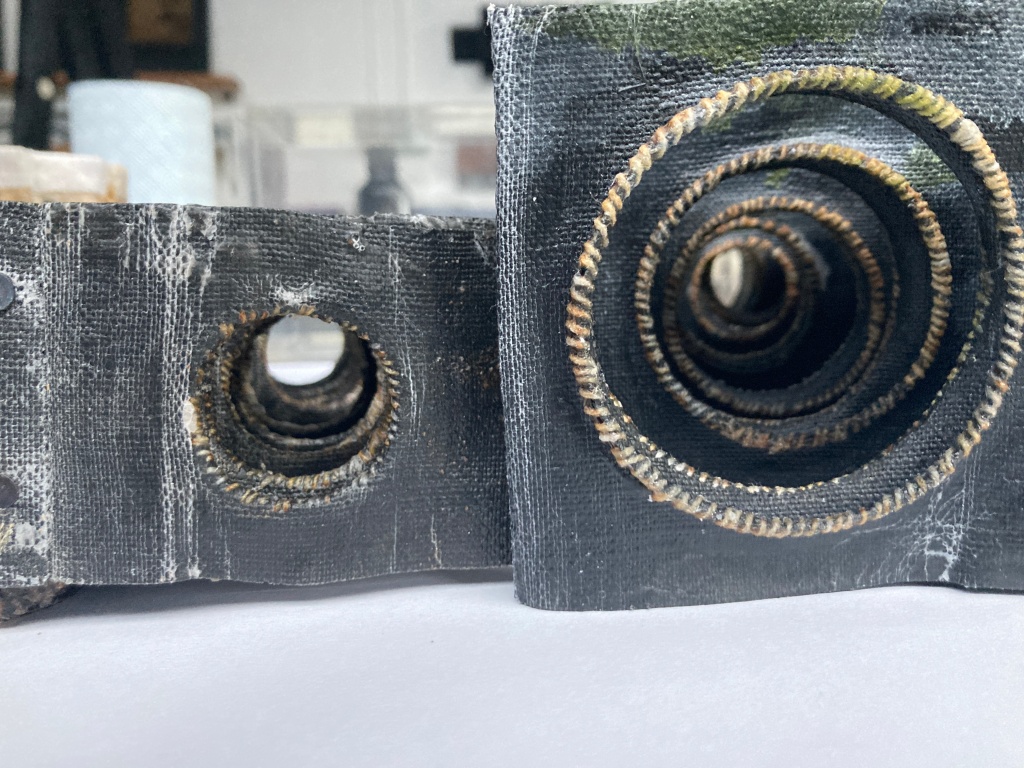

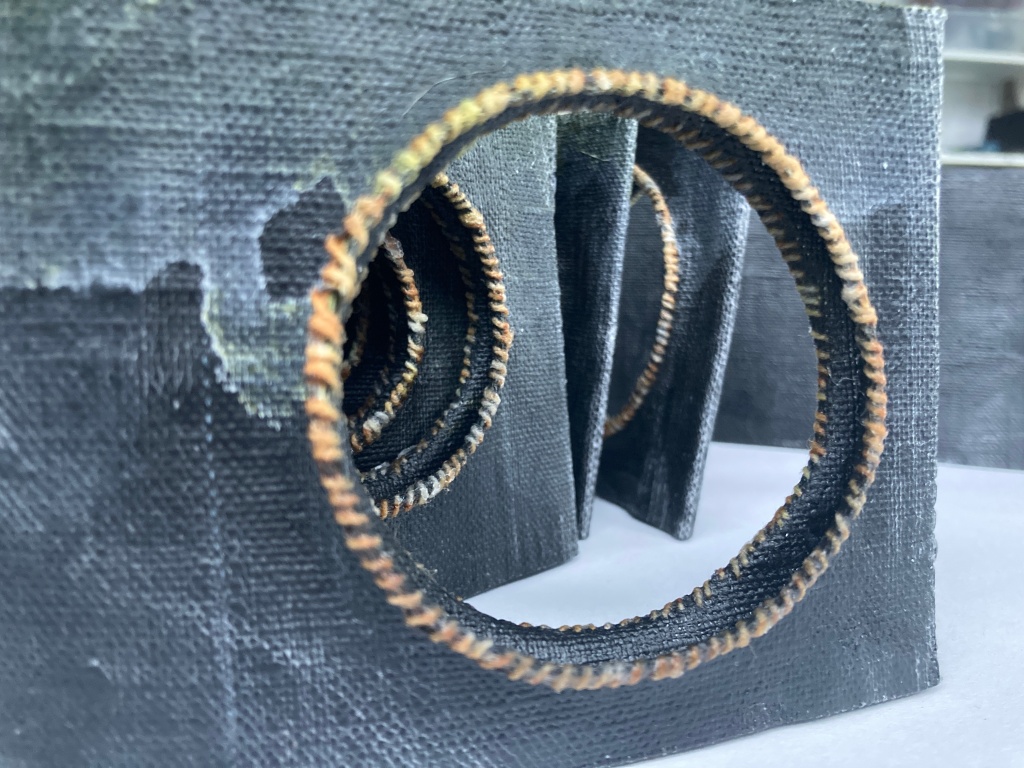

Make holes!

In order to experience your environment, I am asking you to go outside and take some walks. Walking around your ‘place’ is the best way of getting to know it. You will explore it on foot, wandering, and searching out experiences, but I am also going to ask you to sit still and take notice. You’ll sit and look, listen and feel what is going on around you. You’ll pay attention. You’ll notice. You’ll write and draw. And when you get home, I’ll help you to use your noticings to make artworks.

Mark cloth

Lots of marking cloth!

You’ll be drawing and writing, bookmaking, stitching 2D and 3D works and using found objects and playing with interesting materials. I’ll be there all the way through to help and explain, both on the videos and through the dedicated interactive Facebook page where you can ask as many questions as you like.

Stitch

Through the exploration of my place here on the Norfolk coast I help you to use your creative imagination to find your own way of expressing how you experience and react to the place in which you live.

You can find more information here and sign up to reserve a place, or receive a notification when the workshop becomes available.